Bryophytes – World of Wonder

There’s always a gamble: we try to organise events that interest us and that we feel passionate about and presume that others locally will feel the same. So, it’s disappointing when it doesn’t work out, but we must continue to try and hope to get better at our events.

A recent example of this was the Bryophyte Identification Day. I aimed it at professionals, thinking that there must be ecologists (both fully fledged and budding) that would be keen to improve their bryophyte identification for future plant surveys. But sadly no one that booked on would fit this description.

I think I made the wrong decision in terms of who the event should be aimed at, but nevertheless, those that did attend had a truly wonderful time. A simple day, run by bryologist Nick Hodgetts, a very highly experienced professional who’s also, luckily for us, an excellent teacher. The day was split in two with time on the Plock looking at, and collecting, species in the wild and then time in a makeshift lab set up in Skye Bridge Studios for some microscope work. In the field each of us wore a hand lens, a tiny magnifying glass which enables you to magnify plants in the field, and for those rare species that we wouldn’t collect, it still allowed us to see them in close up.

Using a hand lens is a great experience. You lift it to your eye and then bring the subject really close. At times, we would be lying almost in the banking, face inches from the undergrowth as we sought out the mosses and liverworts. And this is one of the factors that I really appreciate about this sort of work: you cannot keep your distance, you really have to get in there, and allow your senses to be filled with the woodland.

It’s the scent that gets me. For some reason, being nose deep in the leaf litter seems to bring a sense of enveloping warmth. The sweet smell of the woodland workings – decay and so-forth – bring a comfort, added to which when all your eye can see is green, your oxytocin goes through the roof. One of our activity leaders came along on the day, and she too was reveling in this secret world. She’s training as a leader in Forest Bathing and having another layer of expertise in the small species of the Plock will enable her to bring a additional level to her activities.

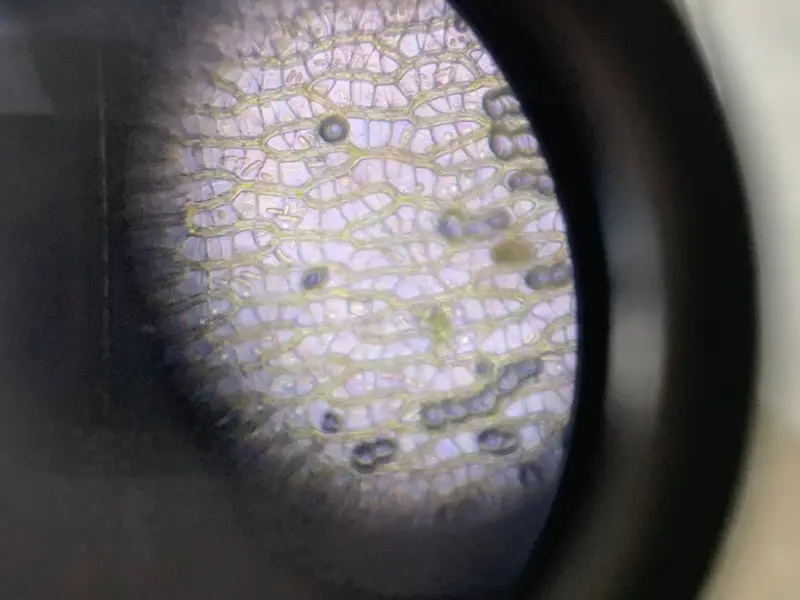

Mosses and liverworts flourish in damp spaces, and as our woodland lingers in one of the wettest parts of the UK, of course we have a rich assemblage of these plants and of all the wet-loving species, perhaps sphagnums are the best known. These are the plants which create peat, and which are beloved by gardeners for their ability to hold onto water. Underneath the microscope we managed to get a good look at the structure of the plant, to see the structures that allow the cells to absorb up to twenty times their own weight in water. Truly remarkable. A new moss to me was a companion moss to the Sphagnums, Aulacomnium palustre, a stunningly ‘fluffy’ moss that was compared to a pine marten’s plumage (yes, it was that magnificent!). The fluff is to draw up water to the top of the plant through capillary action, a very clever companion mechanism to sphagnum’s but as effective at keeping the plant damp.

I was blown away by the linkage between the characteristics of the plant in the field and it under the microscope. I have long been a not-so-secret admirer of two of the Plock’s most common mosses: the beautiful glittering wood moss, Hylocomium splendens and a similar species, Thuidium tamarascum. Together they carpet the woodland of the Plock in bright yellow and green, but we learnt something new from looking at them through the microscope: H. splendens shone under the microscope with light reflected by its elongated cells. These bounce the light off the moss, creating the magical, glittering effect it’s known for, while T. tamarascum has circular cells which create a matt effect on the moss, deadening the light and generating an altogether different appearance when seen en masse.

We hadn’t gotten far onto the Plock before we came across Frullania tamarisci, a liverwort that has pouches underneath the leaves which have the possible function of digesting small animals (digestive enzymes have been found in dissected pouches). We looked at a collected specimen under the microscope and were delighted (and astonished) to see something moving. A greater zoom brought a Rotifer into focus. These miniscule animals are predators that use waving hair-like structures (cilia) on their head to feed single-celled animals such as bacteria into their mouths. Imagine our surprise at finding one residing in our Frullania, and what a treat to discover.

Mosses are easily overlooked, until they are not. Then you realise just what they are: they are habitats. We’ve heard about the home for the Rotifera but imagine my delight at hearing that the capsule that was half-eaten on my specimen of Hypnum andoi had probably been nibbled by a slug or snail! Then, there’s Ulota phyllantha that spreads mainly by asexual reproduction (doesn’t produce spores) and instead spreads through gemmae, part of the plant that easily splits off to be accidentally transported by small foraging birds – think treecreeper – to neighbouring trees, or by slugs and snails to different locations on the same tree.

The example of the half-eaten capsule is an interesting one, as mosses and liverworts have evolved to be unattractive to herbivores and they do this in two very different, very clever ways. In mosses, the cell walls are so thick as to make them unpalatable and not worth the eating. And liverworts contain oil bodies in their cells which are strongly scented, creating an unpleasant taste for nibbling herbivores. These oil bodies are sometimes so huge that they take up a large proportion of the cells, demonstrating how important being unpalatable is to these tiny plants. Sporophytes or capsules, on the other hand, are consumable and so are at risk of being eaten, as seen by the Hypnum andoi mentioned above.

The day passed in wonder and special finds abounded with knowledge enthusiastically shared and expanded upon by Nick: Lepidozia reptans was so tiny that it was hard to see through the handlens, even, but the microscope brought it startlingly into focus. The leaves look like tiny hands, clustered around the central stem; short, spiky Campylopus flexuosus whose long leaves twisted round when dry; Colura calyptrifolia was a new species for the Plock, utterly miniature and utterly beautiful; and, one of my favourites, Plagiothecium undulatum, whose long sinewy branches drape themselves over their habitat.

Imagine how you would have felt to discover all this on the Plock too. An overlooked group of plants that suddenly, when brought into focus, spring into life. The study of micro species is one that can be really meditative: there’s a whole world down there that we hardly notice, hardly think about. But we can enter it easily. All we need is curiosity and a willingness to give it a try.

Image 1: Bryologists in training

Image 2: The beautiful swan head capsules of Hylocomium splendens

Image 3: A chaos of mosses including Rhytidiadelphus squarrosus and Dicranum majus

Image 4: Nick Hodgetts

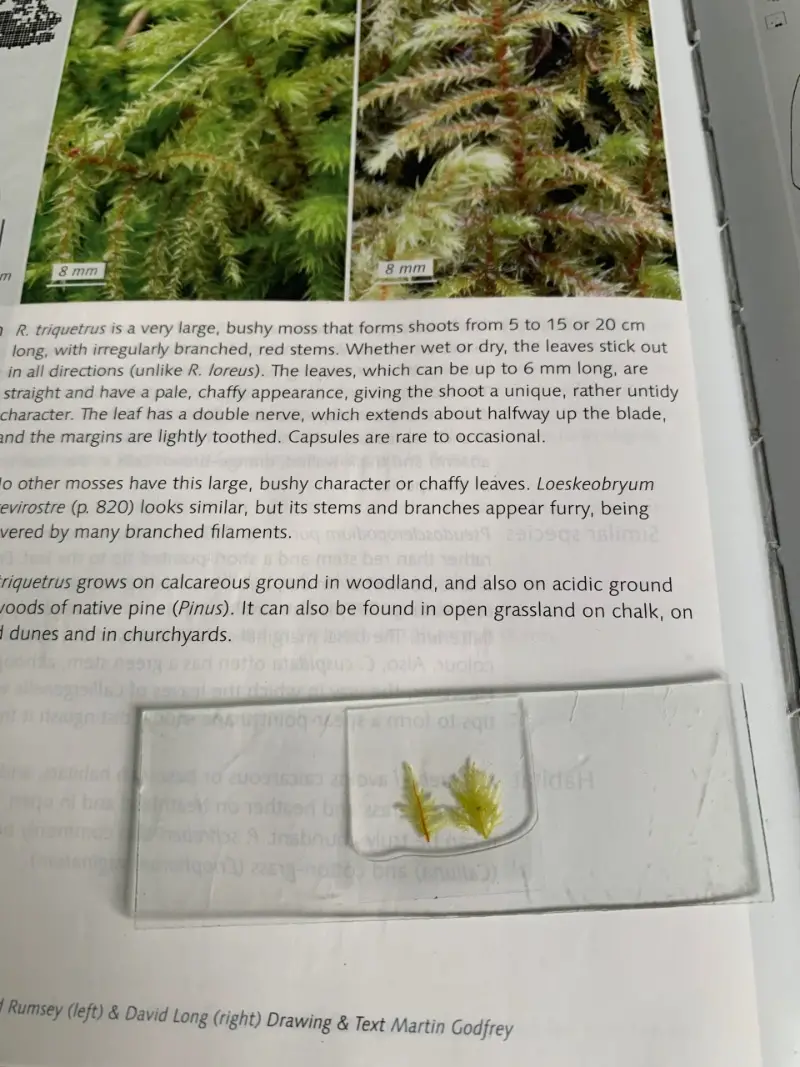

Image 5: H. splendens alongside T. tamarascum (unrelated book page!)

Image 6: The strong cell walls of a sphagnum

Image 7: Vibrant beauty of Thuidium tamarascum

Image 7: Sphagnum quinquefarium

Image 8: Not only liverworts (mainly Plagiochila sp.), but in fact the tiny Wilson’s filmy fern Hymenophyllum wilsonii!